Part 7: Career Readiness Guide: Prepare For Success With Your Liberal Arts Degree | Job Interviews & Pursuing an Independent/Entrepreneurial Career was originally published on College Recruiter.

This is the seventh and final article in this series, click here to go to the first article. If you’re searching for a remote internship, go to our search results page that lists all of the remote internships and other entry-level jobs advertised on College Recruiter and then drill down as you wish by adding your desired category, location, company, or job type.

DURING THE INTERVIEW

Once the big day arrives and your interview begins, you are on the proverbial hot seat. It’s a tough place to be: under inevitable pressure, in the spotlight, with only educated guesses about what you’ll face. Here are some tips that will help you to not only survive, but thrive:

• Arrive 10 minutes before the start time of your interview. Why put even more pressure on yourself by forcing yourself to rush?

• Assume the interview starts the moment you arrive in the building, or even in the parking lot. Hiring decisions can be influenced by the people you interact with other than your interviewer(s)—for example, the front desk staff, or the parking lot attendant. So be polite to everyone.

• Follow the interviewer’s lead, because every interview will vary based on the industry, the organization, and the person:

• Some interviews are conversational in tone, while others are more structured. The key is to match the interviewer’s style.

• Typically in American business culture, making eye contact and shaking hands is expected. But perhaps this isn’t the norm at the organization, or it might not be culturally appropriate. So be adaptable to the situation. Similarly, if shaking hands and making eye contact aren’t culturally appropriate for you, you may want to let the interviewer know in advance or plan for how you’ll approach this issue at the interview.

• Be yourself and show confidence. Don’t worry about giving the “right” answer to each question, because there often isn’t one. The interviewer simply wants to understand who you are and why you’re a good fit for the position and the organization.

• Demonstrate how your experiences and skills (especially your development of the Core Career Competencies) make you a good fit. Tell detailed stories and provide lots of examples. Share your knowledge of the organization and your interest in the position. State how excited you are about the opportunity!

• If you’re ever confused by what the interviewer is asking, simply ask for clarification; it’s OK.

• If you’re asked about something and you don’t have an answer that comes immediately to mind, take time to pause and collect your thoughts. You can even say something like, “I need to think about that for a moment.”

• Sometimes you’ll be in front of a panel of interviewers. Be sure to address the whole panel during your responses, as opposed to focusing only on the person who asked you the question.

• Ask the thoughtful questions you’ve prepared for your interviewer, both to show that you’ve done your research and to determine whether this is a place you could see yourself working someday.

• As the interview is wrapping up, be sure to summarize your qualifications and interest once again, and thank the interviewer(s) for his/her/their time. Ask about the hiring timeline and next steps. And if you don’t already have contact information for your interviewer(s), ask for his/her/their business card(s) so you can follow up with a thank-you note.

AFTER THE INTERVIEW

Once your interview is over, well … it isn’t really over! Sure, you’re out of the hot seat and back in your comfort zone. But you still have some interview-related work to do:

• Assess the interview and your interest in the position and organization. If you’re no longer interested in the opportunity, contact the organization immediately to withdraw from the process.

• Send thank-you notes to everyone who interviewed you. In the note, restate your interest and qualifications, and be as specific as you can about what you enjoyed during the interview. It’s appropriate and professional to send either handwritten or email thank-you notes. If the interviewer(s) indicates that the hiring process is moving quickly, then choose the email option so that your thank-you note arrives before any final decisions are made.

• If you haven’t heard back from the employer within the designated timeframe, send a follow-up email to check on where things are in the hiring process—and to indicate that you’re still interested in the opportunity. It can be as simple as something like this:

Offers

If an interview goes well and you outperform the other candidates for the position, you will receive an offer. Congratulations!

Now what?

Just when you get the very result you’ve been looking for, you have another set of questions to answer. Here’s how you can proceed, methodically and wisely:

• Don’t accept a job/internship offer on the spot. Instead, thank the interviewer immediately to express your gratitude. Then ask what kind of timeline would be appropriate to get back to them with your response. Be sure to follow up with any questions you have about the offer before accepting it (or rejecting it, as the case may be).

• When you’re reviewing an offer—particularly an offer for a full-time, permanent job—look at it holistically: your fit with the organization, your fit with the position, the salary, and the benefits (health insurance, 401(k), life insurance, vacation days, etc.).

Here are a few tools you can use to determine the cost of living and salary ranges based on location, industry, and position:

• Salary.com

• Payscale.com

• U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (bls.gov)

• National Association of Colleges and Employers Salary Survey (look for the periodic news releases summarizing the survey results at naceweb.org/about-us/press)

• If you’re still interviewing with other organizations you’d like to work for, contact them and let them know you’ve received an offer. Then inquire about their timelines so that you can make an informed decision.

• Once you accept a position, contact any organizations you’ve interviewed with to withdraw from their hiring processes. Don’t ever accept a position and then go back later and decline it.

• A career counselor, your advisor, and/or a faculty member can help you navigate the sometimes complicated process of deciding whether or not to accept a position.

Negotiating a Job Offer

Job offers are frequently negotiable, even at the entry level. So even if you are given an offer that meets—or perhaps exceeds—your expectations, particularly in terms of salary, know that you can often negotiate other elements of the offer.

Be sure to review benefits like health care coverage, vacation time, sick time, and parental leave policies, as well as typical starting salaries for people in the type of position you’re being offered. That way you’ll be better prepared to advocate for what you want during negotiation.

Some other key tips on negotiation:

• Remain professional, friendly, and open. Use language that demonstrates that you’re simply having a conversation—and that you are asking, not assuming (or, worse, demanding).

• Cite specific reasons for why you’re asking for something more, and have some research ready to back up your statements.

• Always give a salary range, not a firm number.

Here’s an example of what your approach might sound like:

Declining a Job Offer

What if it turns out that you don’t want the job/internship you’ve been offered? That’s OK—you have your reasons. You just have to be professional and gracious in declining the offer.

Here’s how:

• Let the organization know as soon as possible, because the people there are waiting for an answer from you before they can move forward.

• Be polite and sincere when you decline. Be sure to thank the people involved for considering you, and let them know your reason(s) for not accepting the offer.

One final, but critically important, note: Do not decline an offer after you have already accepted it. Employers/recruiters have a word for this aggravating practice—reneging—and it happens to them more than you might think. They make a job/internship offer to a college student, and the student accepts it. Then the student comes back a day or a week or even a month later and says, essentially: “I’ve changed my mind: Thanks, but no thanks.” Suddenly the employer’s hiring problem has returned, unexpectedly.

If you’re the student who has reneged, don’t expect to receive any more consideration from this organization. But it gets worse, potentially: Employers know each other, and word may spread that you are someone who will renege on a job/internship offer. Moreover, your fellow students— including the many who don’t even know you—could be somewhat tainted as well. The employer might think: “I’m not going to hire any more students from _______ ” or “I’m not going to consider any more students from the ______ department at Sample College.”

So don’t accept an offer unless you’re really accepting it. Don’t accept one and then continue looking for a better job/internship opportunity. If you’re going to decline an offer, decline it outright.

PURSUING AN INDEPENDENT/ENTREPRENEURIAL CAREER

Maybe the whole idea of one day pursuing a “job,” in the traditional sense, just doesn’t quite resonate with you. Perhaps you have a more independent/entrepreneurial career path in mind—starting a small business (either a solo operation or a larger enterprise), freelancing, doing contract work, launching a nonprofit organization, performing, running for political office, or doing something even more tailored to you and your unique blend of interests, values, and strengths.

Or maybe you’d actually prefer to choose “d) all of the above” on the career front: You’d like to pursue a job in the traditional sense and also pursue something more independent/entrepreneurial as a “side-hustle” and be part of the gig economy.

Then again, maybe you see yourself mixing together several different types of freelance/contract opportunities to create your own blended portfolio career.

Or maybe you’d like to start out your career working for someone else, then transition later to somehow working for yourself.

Whatever your specific independent/entrepreneurial vision, know that you are far from alone, especially these days:

• A 2018 NPR/Marist Poll showed that “a notable proportion of American workers”—20 percent—are contract workers.

• A 2019 study by freelancing website Upwork and independent workforce association Freelancers Union found that 35 percent of the U.S. workforce are freelancers. Of those, 28 percent freelance full time.

• Many alumni have taken the independent/entrepreneurial path after graduation. (Note: Your advisor, a career counselor, and/or a faculty member can help you identify them and find a way to contact them.)

As a liberal arts student, you are well-suited to the independent/entrepreneurial path. You can deal with ambiguity. You can think critically. You can spot opportunity. You can envision and create and execute. And you can present yourself, your strengths, and your ideas compellingly, pulling all the while from the Core Career Competencies that you have been developing throughout your college experience.

But you still might feel like a fish out of water—like you’re the only liberal arts student who has ever wanted to pursue an independent/entrepreneurial career path (either full-time or part-), and that you are therefore on your own when it comes to making it a reality.

You’re not. And you’re not.

Guidance for the Independent/

Entrepreneurial Path

The individual nature of the independent/entrepreneurial career path makes it virtually impossible to adequately cover in a guide like this one. But we want to stress once again that going your own way is a valid, worthy, realistic, and viable pursuit—and that we can help you pursue it.

Here are some key tips to consider:

Talk to a Career Counselor, Your Advisor, and/or a Faculty Member.

This is a time when you need someone who will listen closely—to your entrepreneurial aspirations, fears, and everything in between— and help you process them and start doing something about them. Every person’s situation is different and complicated; yours will be too. All the more reason to work with someone who can help you directly and, just as importantly, guide you to other resources (people and informational) that can help you as well.

Talk to Your Professors Who Have Independent/Entrepreneurial Connections and Experiences.

Many professors have their own personal experience with independent/entrepreneurial activities (current or past), and many more keep in touch with former students who have gone on to pursue independent/entrepreneurial career paths. The very best way to discover how to do something is to talk to people who have already done it. If they share a connection with you, that’s even better.

Talk to Alumni Who Have Independent/Entrepreneurial Connections and Experiences.

Search for alumni profiles and groups on career networking website LinkedIn (linkedin.com). You could begin your discussions with an alum via email and then perhaps talk on the phone or even meet to learn more.

Talk to Others in Your Life Who Have Independent/Entrepreneurial Connections and Experiences.

Family members, friends, fellow students, work colleagues, old teachers, neighbors—some of them are either doing what you want to do or know someone who is.

The independent/entrepreneurial career path isn’t an easy one. But as many liberal arts students before you have discovered, it can certainly be a rewarding one—and an impactful, exciting way to leverage your liberal arts advantage.

PURSUING EDUCATION

PLANNING FOR GRADUATE SCHOOL

Maybe you’ve been thinking about graduate school for years. Or maybe it’s a brand new idea. Either way, you need to ask yourself one key question before you invest all the time, energy, and money involved, both in applying for graduate school and in succeeding once you get there: Is graduate school right for me?

DECIDING IF GRAD SCHOOL IS

RIGHT FOR YOU

Before deciding if graduate school is right for you, you need to know that there are two types of graduate school programs. One type is professional and focused on giving you the skills and qualifications necessary to succeed in a profession; think of an MBA program or graduate degrees from medical or law schools. These programs are usually very structured and career focused. Other programs, typically those that end in a Ph.D., are more academically focused and aim mainly to prepare future professors and researchers. These programs are typically less structured and build around your own academic interests.

Here are a few questions that will help you make an informed decision about your potential graduate or professional school pursuits. You’ll be able to answer some of them yourself, quite easily. For others, you’ll need to do some research and perhaps even talk to graduate program staff members or faculty.

Start with this essential question: Why am I interested in graduate school?

Weak Answers

• I want to take a break from a tough job market.

• I want to figure out a new career path or find career direction. (There are cheaper ways to do that!)

• I don’t know what else to do

Strong Answers

• I’m genuinely interested in my field and passionate about pursuing new knowledge and expertise in a very specific area.

• My career goals require a graduate degree.

• I have the resources I need (time, academic record, money, energy) to be successful in a graduate program.

If you do ultimately decide that you’d like to go to graduate school, the next question to ask yourself is: When is the right time? You could go right away, or you could wait:

Reasons Why You Might Want to Go to Graduate School Right Away

• You have momentum and a desire to continue being a student.

• You may have more flexibility, with fewer family, work, or financial commitments.

• The degree might be necessary to help you get the job you want, or it could help speed career advancement in your chosen field.

• You currently meet the requirements for admission (i.e., the program doesn’t require extensive work experience before you apply, and your GPA/test scores fit within the program’s criteria).

• You are willing and able to make the financial investment now.

Advice From Liberal Arts Grads:

The More You Plan, the Less Stressed You Will Be

“Create a detailed plan of the steps you need to complete in the process of applying to graduate school so that you can maintain your stress levels.”

Reasons Why You Might Want to Wait to Go to Graduate School

• You need more time to be sure of your career goals.

• You currently do not meet the requirements for admission (i.e., the program you’re targeting requires more work experience than you have, or higher GPA/test scores than you have).

• You don’t yet have the financial resources to invest in another degree.

• You can save money by waiting, or you may find an employer who would help you pay for your program.

• You find value in taking a gap year(s) to gain experience that may help strengthen your graduate school application.

• A break might boost your motivation for further study.

Graduate School Application Timeline

Once you’ve decided that you will in fact go to graduate school, keep in mind that you should begin the application process at least one year before you plan to start your chosen program.

Here’s a planning chart with approximate timelines. Deadlines for specific programs can vary greatly, so be sure to look them up well in advance.

Spring of Junior Year, or 15 to 18 Months Prior to Enrollment

• Reflect on your personal and professional goals to determine if graduate school is right for you.

• Discuss your plans and options with trusted mentors, advisors, instructors, family members, alumni, etc.

• Identify the key considerations you’ll be looking for in a graduate program (e.g., location, cost, program offerings, faculty, ranking, financial aid availability).

• Begin researching and evaluating graduate programs.

Summer Before Senior Year, or 12 to 15 Months Prior to Enrollment

• Contact admissions officers, faculty members, and students/alumni from your programs of interest to get more information, determine potential fit, and build relationships.

• Get organized! Learn about the admissions criteria and timelines of your applications, and keep track of your deadlines.

• Begin narrowing down your list of potential programs (select two to five that range in competitiveness).

• Study and register for entrance exams, if necessary.

• Write drafts of your personal statement and résumé/CV (curriculum vitae).

Fall of Senior Year, or 10 to 12 Months Prior to Enrollment

• Take required entrance exams, if necessary.

• Order your official transcripts.

• Start gathering necessary application materials, and get constructive feedback on your personal statement and CV (curriculum vitae)/résumé—early!

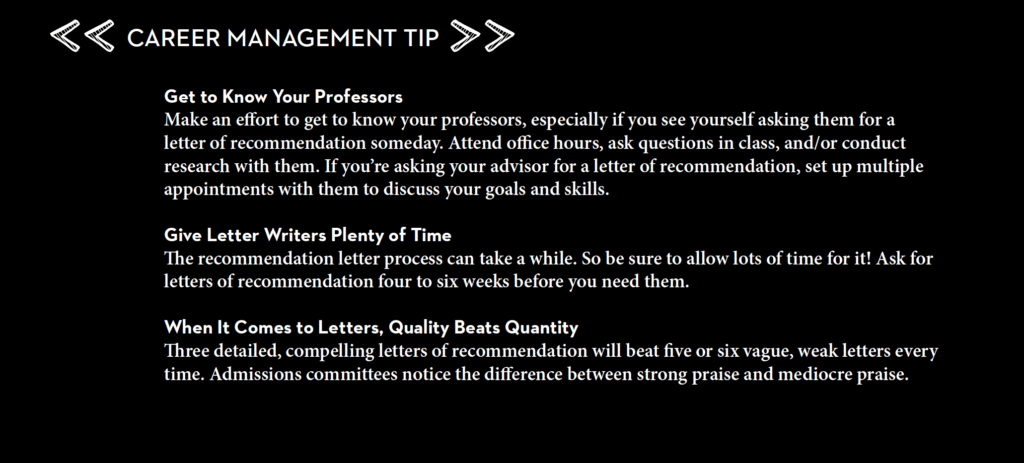

• Ask for letters of recommendation (from faculty members, instructors, advisors, and supervisors) at least four weeks before you need them.

• Learn about the funding/financial aid opportunities for the different graduate programs you’re exploring.

• Submit your application(s) and supporting materials by the deadline(s)!

Winter/Spring of Senior Year, or 6 to 10

Months Prior to Enrollment

• Send thank-you notes to the people who wrote recommendations for you.

• Prepare for and complete interviews.

• Patiently await admissions decisions.

• Contact schools about the possibility of visiting. A personal visit can often improve your chances of being accepted. Departments/programs will sometimes help with travel expenses, so ask about that possibility.

• Consider multiple options and decide.

RESEARCHING AND EVALUATING GRADUATE

PROGRAMS

Reflect

Before you select a graduate program, reflect on what you’re really looking for in one. Common considerations might include location, class size, ranking, programs, faculty, research opportunities, financial support, access to professionals, internship possibilities, and licensure.

Talk with People!

You can usually contact a graduate school’s admissions office for answers to your basic questions, and they will often give you contact information for graduate program faculty and/or students as well.

However, graduate programs vary considerably, and not all schools have admissions staff. Some graduate programs will instead offer a faculty member or a graduate coordinator as your primary contact. These key people can help you plan a visit to the campus. While you’re there, you can arrange to sit in on classes and labs, if possible, and meet program faculty, staff, and students.

When you ask questions about grad schools and programs, be open to different viewpoints and listen for common themes that come up. Take notes. And if you arrange a program visit, prepare in advance the questions you’d like to ask while you’re there.

Graduate School Programs:

What Questions to Ask Questions About Admissions

• What application deadlines should I be aware of?

• What is the undergraduate GPA range and preference for this program (sometimes referred to as the middle 50%)?

• If an entrance exam is required, what is the preferred test score (for standardized tests such as the GRE, GMAT, LSAT, or MCAT)?

• What percentage of students who applied last year were admitted?

• What additional factors have the most impact on acceptance into this program?

• What previous experience/knowledge (if any) is preferred for this program?

Questions About the Program

• Are there prerequisite courses I need to complete before I start this program?

• What are the degree requirements? How many required and elective classes are there?

• How long do students typically take to complete this program?

• What areas of concentration are available?

• How does the program’s department evaluate student progress?

• What kind of thesis and examinations are required?

• What practical experience are students expected to complete?

• What professional development opportunities exist for students?

• What kind of licensure/certification will I be eligible for after completing the program?

• What support is provided to help students fulfill the experiential components of the program?

• What kind of job search support is provided by faculty members?

• What types of careers do alumni go into with this degree?

• Can I sit in on a class to observe the program in action?

Questions for Program Faculty

• What is most important to you in an advisee?

• When and how is an advisor selected? How difficult is it to switch advisors once you’re into your program?

• How many full- and part-time faculty members teach in this department?

• What diversity exists within the faculty?

• What experiences have the faculty members had outside academia?

• What opportunities exist to work with faculty on their research or do research on my own?

• What are the research priorities of the faculty?

Questions for Students Enrolled in the Program

• How available is your advisor?

• How would you characterize the departmental culture?

• What is the actual time commitment for a teaching assistant or research assistant position?

• Is the funding/stipend provided by the department enough to live on?

• How do students interact with each other inside and outside the classroom?

• What are some of the politics or current issues within the department?

• What diversity exists within the student body?

• How much support do students receive in developing their own approach to the field?

• How often do students present their work at professional conferences?

• What are the courses like?

• Are there opportunities to engage in research?

Questions About Finances and Resources

• How available are teaching assistantships, research assistantships, or fellowships?

• What other helpful resources are available for students (e.g., graduate student housing, medical insurance, child care, fitness facilities)?

• Are students guaranteed funding throughout their time in the program, or is it awarded on a yearly basis?

Narrow Your Options

Use the information you’ve gathered to narrow the list of programs you’d like to apply to. Often, students will end up applying to three to five programs, but your own number may be higher or lower. Whatever you decide, be sure you apply to a balanced list of programs that range in their competitiveness; target some programs that are well within your admission and financial reach, as well as alternative options that may be more competitive.

APPLICATION MATERIALS

When you’re applying to graduate or professional school, be sure to contact each program directly to find out its specific application procedures. Visit each institution’s website for detailed information about the application process.

Most schools and programs require applicants to complete multiple applications, forms, or essays. So be sure to thoroughly review all of the application instructions.

Among the items you’ll commonly need to submit with your graduate school applications:

• Entrance exam results (often reported by an official service).

• Letters of recommendation.

• A personal statement.

• An official transcript.

• Résumé/CV (curriculum vitae).

• Completed application form.

Entrance Exams

Many graduate and professional schools require applicants to take some type of entrance exam. So as you research graduate schools and programs, be sure to pay close attention to which test(s), if any, is required.

Testing centers often have wait times of two to four weeks for the popular exams, so plan accordingly. The Educational Testing Service website (ets.org) is an excellent resource for general information.

There are many ways you can prepare for entrance exams. First, consider your learning style, financial means, resources, and timeline. Then, of course, study! Here are some ways you can do so:

• Review the actual exam. Go over an old copy of the exam to familiarize yourself with the skills it assesses and the types of questions it asks. You can usually find old copies of the exam in the test’s registration manual, on the test company’s website, or in study guides. Once you’re familiar with the actual exam, you’ll be better prepared to choose your study techniques and priorities.

• Form a study group. Ask friends or classmates to study with you. Quizzing each other will help you learn from each other and make the process a little more fun.

• Use study-guide books. Any good bookstore will have study guides covering the major graduate/professional school admissions tests.

• Take advantage of test prep resources. Companies like The Princeton Review (princetonreview.com) and Kaplan (kaplan.com) offer prep classes for the most common entrance exams, such as the GRE. One cautionary note, though: These courses can be expensive. And while some students really like them and find them helpful, others think they’re unnecessary. Before spending money (to say nothing of time and energy) on a test preparation course, thoroughly research it along with the outcomes you can expect from it. Ask your advisor, a career counselor, or a faculty member to help you.

Letters of Recommendation

Letters of recommendation are a key part of the application process for graduate and professional school programs. These letters should describe—and give examples of— your strongest qualities, your best skills/competencies and abilities, your commitment to a particular field, and your potential to contribute to the target program’s field of study and related careers.

Who should write letters of recommendation for you? Here are some tips for picking the right people:

• Approach potential writers who will give you a solid recommendation. Ask them directly if they would be willing to write a letter that is reflective of who you are and the good work you do.

• Focus on people who know you well academically or professionally: faculty members, supervisors, coworkers, or advisors. Family members are usually not appropriate.

Remember, too, that your prospective letter writers have busy jobs, appointments, and possibly other students seeking recommendations as well. So do everything you can to make your request simple for them. Give them everything you can from the following list:

• Relevant information about the school(s) or graduate program(s) you’re applying to.

• Your thoughts on what you see as your strongest qualities and skills/competencies (especially in the context of the Core Career Competencies that signify your career readiness).

• A copy of your résumé/CV, and/or a printed summary of your involvement in student organizations and groups.

• A list noting which academic courses you’ve completed and how well you’ve done in them.

• A sample of your personal statement, if you wrote one for your graduate school applications.

• Pre-addressed envelopes for each school/program you’re pursuing.

A few other key tips:

• Be sure that all of your recommendation letters appear on letterhead.

• Give your letter writers an early deadline, occasionally check in with them, and offer them reminders as needed.

• Keep your letter writers informed about the application process.

• Stay organized by carefully tracking who your letter writers are, what application deadlines you’re dealing with, and who you have followed up with or still need to follow up with.

Personal Statements

For most graduate school applications, you’ll be required to write a personal statement (also known as a statement of purpose). This is simply an essay in which you explain why you want to pursue a particular graduate program and why you’d be a good fit for it. (The piece also offers the program faculty a sample of your writing.) As you prepare to write your personal statement, think carefully about questions like these:

• What are your motivations for pursuing graduate school?

• What are your interests, skills/competencies (particularly in the context of the Core Career Competencies), and goals? How do they relate to the graduate program(s) you’re pursuing?

• How do your personal goals match with the institution(s) or program(s) you’re considering?

• What makes you a strong candidate for the graduate program(s) you’re targeting?

• What makes this particular kind of program a good fit for you? (For example, why law school instead of public policy?)

• How should you assess different graduate programs/schools? What are the criteria for acceptance? What are the values of each program and institution? What themes are expressed by students and staff from these programs/institutions?

Once you’ve answered these questions thoroughly, you can begin writing your statement. Use the information you’ve gathered through self-reflection and research, and thoughtfully explain how the program you’re targeting fits you and your long-term goals. These tips will help:

Follow the Directions on Each Specific Application

• Read the instructions very carefully. Follow the required format, as well as the required word count or page limit.

• Read each question closely, and be sure to answer each one.

• Avoid writing vague or generic-sounding personal statements. They’re ineffective.

• If the school/program application offers no specific questions to address in your personal statement, focus on the experiences, motivations, and goals you have that relate to the program.

• If you’re creating personal statements for multiple schools/programs, customize each one to reflect your research and interest in a particular program.

Mention the Research You’ve Done on the Program or School:

• You view this program as a good match for you. Explain why.

• What opportunities does this program offer? What is it known for? Discuss why it matters to you.

• What faculty members do you hope to work with, and why?

• Use anecdotes from your life to tell the admissions committee who you are. Share stories about yourself, and relate them to the program and your long-term career plans.

• Emphasize what’s unique about you— for example, classes you’ve taken, professors you’ve worked with, or events you’ve attended. You can also highlight projects, volunteer positions, jobs, or internships that relate to your goals.

• Demonstrate that you have a realistic sense of the field and the training required for it. Provide examples of how you’ve prepared yourself for this field (for example, how you did research, performed volunteer work, or pursued related experiences).

• Don’t explain the field or program. The reader(s) of your personal statement will already be an expert.

• Use your statement to highlight information that isn’t covered in other parts of your application.

• Draw the reader in with a strong opening statement and compelling first paragraph. Your application is one of many, and a solid start will help you stand out in the applicant pool.

• Discuss what the program will gain by accepting you.

• Keep your tone positive. This is not the place to make excuses for shortcomings in your background or application, or for poor grades. It is OK, though, to show how you’ve grown from your

experiences. Doing so will showcase your self-awareness and maturity

• If there was a short period of time when you did poorly in school or withdrew from classes, and it was due to extenuating life circumstances (e.g.,you were ill, there was a death in your family), you can address the issue in an addendum. Make an appointment with a career counselor, your advisor, or a faculty member for guidance on writing an addendum.

• Come across as genuine, realistic, unique, and excited.

• Avoid romanticizing your plans. Talk about realistic ways you expect to contribute to the field.

• Balance your enthusiasm, anecdotes, and self-marketing with practical information.

• Avoid cliches like “I’ve always wanted to…” or “I like to help people.” They’re meaningless.

Don’t Stop Once You Have a Draft Ready

• Edit and proofread your statement as it stands so far. Are you communicating exactly what you want to say?

• Does the statement look professional, and is it well written? Look at grammar, font size, aesthetics, spelling, and format.

• Include your name as a header on each page.

• Have a career counselor, your advisor, and/or a faculty member review the statement.

Done? Almost.

Before you submit your finalized personal statement with your other application materials, proofread it one last time! Have someone else proofread it too. (Note: Read your statement aloud; you’ll catch more errors that way, and you’ll uncover more awkward words and phrases, too.)

Then send it off—and congratulate yourself!

Advice From Liberal Arts Grads

Use All Your Resources to Discover the Path That’s Best for You

“Use your resources, start imagining your post-graduation career, how you can use your education and experience. Look at job postings, speak with current people who work in your field, discover what further education/experience is needed to pursue your career post-graduation. Get involved in internships or volunteer experiences that are related to your intended field.

Most of all, take your time in deciding what field is best for you. Experiment as needed in different interests. Don’t let outside or internal pressure force you into a job that is less than what you hoped for. You have time to discover what path is best for you. Good luck!”

MAKING A DECISION

You submitted all of your graduate/professional school application materials weeks or months ago, and now you’ve been notified about a decision by the admissions committee. Maybe you’ve received acceptance to your top choice, or an alternate choice. Perhaps you’ve been put on a waitlist. Or maybe you received a rejection letter.

Whatever the outcome, you still have your own decision to make. So reflect back on your reasons for applying to graduate school in the first place, as well as your needs and priorities:

• If you’ve received a rejection and you’d like to reapply in the future, speak with an admissions representative from your target school/program to learn how you can strengthen your application next time.

• If you’ve been put on a waitlist, consider how long you’re willing to wait before pursuing other options.

• If you’ve received an acceptance, congratulations! Now, make sure to consider factors like cost, financial aid, location, opportunity, and personal fit to weigh the pros/cons of accepting the offer. If you decide to go ahead, pat yourself on the back for a job well done! You’re on your way.

— This is the seventh and final article in this series. This series of articles are courtesy of the collective expertise of the staff in the Office of Undergraduate Education and Career Services in the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota.